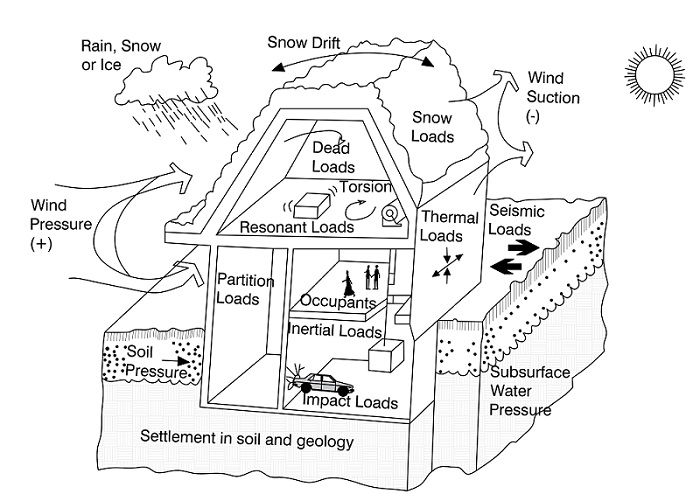

Before designing any structure or elements such as beams and columns, it is essential to first determine the various natural and man-made loads acting on them. The primary function of any structure is to carry loads and transmit forces. These loads can arise in various ways and depend on the purpose for which the structure is built. Loads induce different types of actions, such as deformations, stresses, or displacements, on the structure. Determining the appropriate loads for which a given structure must be designed is a complex task. Decisions need to be made regarding the types of loads the structure may experience during its lifetime, as well as the possible combinations of these loads. Below are some of the key types of loads that need to be considered.

1. Dead Load

The self-weight of the structural element and the permanent loads on the structure are known as dead loads. Dead load is fixed in magnitude and direction.

Determining the dead load requires estimating the weight of the structure along with its associated non-structural components. This includes the weight of slabs, beams, walls, columns, partition walls, false ceilings, facades, claddings, water tanks, stairs, brick fillings, plaster finishes, and other services such as cable ducts, water pipes, etc.

The dead load is obtained by multiplying the unit weight by the volume of the element:

Dead Load = Unit Weight × Volume

Unit weights of different materials are provided in various codes and standards. For dead load calculations, refer to IS 875 (Part I) – 1987 and EN 1991-1-1.

2. Imposed Load

Imposed loads, also referred to as live loads, are gravity loads other than dead loads. These include items such as occupancy by people, movable equipment, furniture, stored materials like books, machinery, and snow. The magnitude of imposed loads varies depending on the type of building, such as domestic, office, or warehouse buildings, and can change over time and across different spaces.

Live loads are generally expressed as static loads, although minor dynamic forces may also be involved. The imposed loads applied to the floor of the structure can be obtained from standards such as BS 6399 Part 1 (1996), ASCE 7-16, or IS 875 (Part 2) – 1987.

3. Wind Load

Wind load refers to the force or pressure exerted by the wind on a structure. Wind produces static, dynamic, and aerodynamic effects on the structure. When deflection occurs in a structure as a result of wind action, both the dynamic and aerodynamic effects should be studied in addition to the static effects.

The wind pressure or load acting on the structure depends on several factors, including:

- Velocity and density of air

- Height above ground level

- Shape and aspect ratio of the building

- Topography of the surrounding ground surface

- Angle of wind attack

- Solidity ratio or openings in the structure

- Susceptibility of the structural system to steady and dynamic effects induced by the wind load

Based on these factors, the wind can create either positive or negative pressure on the sides of the building. The response to the load depends on the type of structure.

Various standards are available for calculating wind pressure on structures. Some of the key codes for reference are EN 1991-1-4, IS 875 (Part 3), and BS 6399-2 (1997).

4. Earthquake Load

Earthquakes cause the ground to shake in all directions, with tremors lasting from a few seconds to several minutes. Earthquake loads arise due to the inertia forces produced in a building as a result of seismic actions. These are dynamic loads and are directly proportional to the mass of the structure.

When the earthquake load exceeds the moment of resistance offered by the structure, damage or collapse may occur. Additionally, the earthquake can reduce the bearing capacity of the soil, leading to settlement and potential collapse of the structure. The response of the structure to ground vibrations depends on factors such as the foundation soil, the mass of the structure, and the duration and intensity of the ground motion.

Seismic forces acting on a structure can be computed using the following methods:

- Response spectrum method

- Seismic coefficient method

Key codes for reference include IS 1893 (Part 1), EN 1998-1 to 6, and ASCE/SEI 7.

5. Impact Load

Impact loads are sudden or rapid loads applied to a structure over a relatively short period of time. These loads generate larger stresses in structural members compared to those produced by gradually applied loads of the same magnitude.

Examples of impact loads include the weight of falling objects, loads from moving vehicles, or the forces generated by vibrating machinery.

Impact loads can be converted empirically into equivalent static loads using an impact factor, which is typically expressed as a percentage. Impact loads are particularly important in industrial buildings, where machinery is mounted on floors, as well as in bridges.

Codes for reference regarding the impact factor include IS 875 (Part 2) and ASCE/SEI 7-16.

6. Snow and Ice Load

Snow load, or ice load, results from the accumulation of snow and is considered primarily in regions prone to heavy and frequent snowfall.

The procedure for calculating the snow load on a roof involves multiplying the ground snow load (corresponding to a 50-year mean return period) by a coefficient. This coefficient accounts for factors such as roof slope, wind exposure, non-uniform snow accumulation on pitched or curved roofs, multiple series or multi-level roofs, and roof areas adjacent to projections.

It is important to note that maximum snow and maximum wind loads are not considered to act simultaneously. Wind-induced drift formation should be considered, as most snow-related roof damage occurs due to drifted snow. The shape of the roof also plays a significant role in calculating snow load. For example, on a flat roof, snow tends to accumulate, whereas on a pitched roof, it is more likely to slide off.

Standards that address snow load calculations include IS 875 (Part 4), EN 1991-1-3, and ASCE/SEI 7-10.Snow load, or ice load, results from the accumulation of snow and is considered primarily in regions prone to heavy and frequent snowfall.

The procedure for calculating the snow load on a roof involves multiplying the ground snow load (corresponding to a 50-year mean return period) by a coefficient. This coefficient accounts for factors such as roof slope, wind exposure, non-uniform snow accumulation on pitched or curved roofs, multiple series or multi-level roofs, and roof areas adjacent to projections.

It is important to note that maximum snow and maximum wind loads are not considered to act simultaneously. Wind-induced drift formation should be considered, as most snow-related roof damage occurs due to drifted snow. The shape of the roof also plays a significant role in calculating snow load. For example, on a flat roof, snow tends to accumulate, whereas on a pitched roof, it is more likely to slide off.

Standards that address snow load calculations include IS 875 (Part 4), EN 1991-1-3, and ASCE/SEI 7-10.Snow load, or ice load, results from the accumulation of snow and is considered primarily in regions prone to heavy and frequent snowfall.

The procedure for calculating the snow load on a roof involves multiplying the ground snow load (corresponding to a 50-year mean return period) by a coefficient. This coefficient accounts for factors such as roof slope, wind exposure, non-uniform snow accumulation on pitched or curved roofs, multiple series or multi-level roofs, and roof areas adjacent to projections.

It is important to note that maximum snow and maximum wind loads are not considered to act simultaneously. Wind-induced drift formation should be considered, as most snow-related roof damage occurs due to drifted snow. The shape of the roof also plays a significant role in calculating snow load. For example, on a flat roof, snow tends to accumulate, whereas on a pitched roof, it is more likely to slide off.

Standards that address snow load calculations include IS 875 (Part 4), EN 1991-1-3, and ASCE/SEI 7-10.

7. Other loads and effects

7.1 Foundation Movements

Foundation movements result in absolute settlement, vertical tilt, and angular distortion, which can lead to cracking in the building. The permissible values for total settlement, differential settlement, and angular distortion are provided in IS 1904.

7.2 Thermal Actions

Thermal load is defined as the effect of temperature on buildings and structures. This can include outdoor air temperature, solar radiation, underground temperature, indoor air temperature, and heat generated by equipment inside the building. Thermal actions induce additional deformations and stresses in the structure. These effects depend on the geometry of the element and the physical properties of the materials used in construction. Thermal movements cannot be restrained, so the design must allow for thermal expansion or contraction. If not accounted for, stresses in the restraints or within the structure could lead to catastrophic failures. The codes for reference include EN 1991-1-5 and ASCE/SEI 7-15.

7.3 Soil and Hydrostatic Pressure

The pressure exerted by soil, water, or both must be considered when designing structures below ground level, such as basements and retaining walls. When a portion or all of the soil is below the free water table, lateral earth pressure is evaluated by considering the reduced weight of the soil due to buoyancy and the full hydrostatic pressure. All foundation slabs and footings located below the water table should be designed to resist a uniformly distributed uplift equal to the full hydrostatic pressure.

7.4 Construction Loads

Construction loads are the loads imposed on a partially completed or temporary structure during the construction process. These include the loads from materials, personnel, and equipment placed on the structure during construction. The standards addressing construction loads include ASCE 37 and EN 1991-1-6.

7.5 Flood Load

The changing global climate has led to unpredictable flooding in several parts of the world, making it essential to protect structures against such events. Storm-induced erosion and localized scour can lower the ground level around building foundations, reducing their load-bearing capacity and resistance to lateral and uplift loads. Provisions related to flood loads on structures can be found in ASCE/SEI 7-10 and ASCE 24-05.

7.6 Blast Loads

Blast loads are a rare but significant type of load that acts on structures for a short duration. The detonation of blasting materials releases a large amount of energy, which is converted into thermal and kinetic energy. This results in pressure waves being generated. The wave propagates through the air, encircling the structure and impacting all its surfaces, causing the entire structure to be exposed to the blast pressure. The magnitude and distribution of the blast load depend on several factors, including the characteristics of the explosive material, the amount of released energy (size of detonation), the weight of the explosive, the detonation location relative to the structure, and the intensity and magnification of pressure during interaction with the ground or structure. Reference codes for blast loads include ASCE/SEI 59-11, IS 4991-1968, and IS 6922.