When it comes to sustainable design, the most powerful step we can take is also the simplest: use less. Reducing material use lowers embodied carbon, cuts overall emissions, and results in fewer greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere. While choosing low-carbon materials and exploring carbon offsetting are important, the most impactful action begins with a simple principle—use less

Cement and Concrete

Concrete is the most widely used man-made material in the world, second only to water in total consumption. Its importance in modern society cannot be overstated. From housing and roads to bridges and dams, concrete plays a central role in economic development, public infrastructure, and the built environment. As we look toward a future shaped by low-carbon development, concrete will remain a foundational material in delivering sustainable, long-lasting infrastructure.

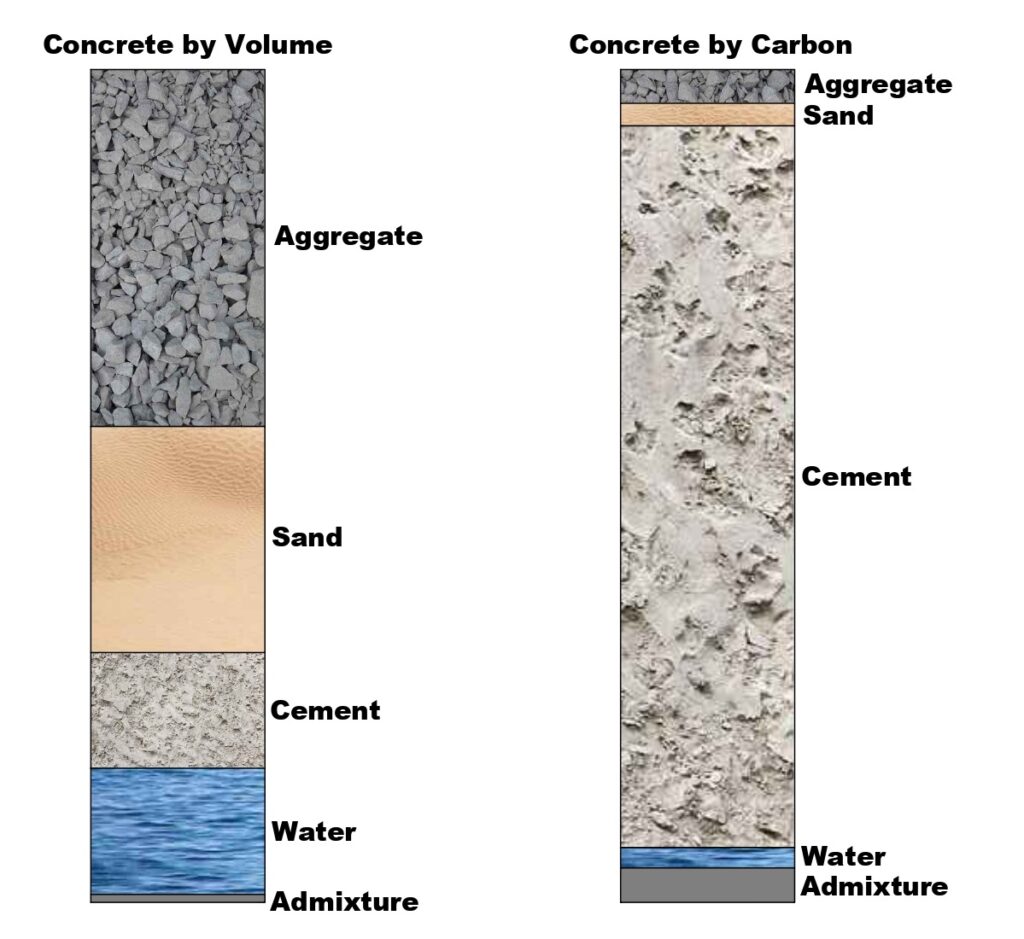

Cement is the key ingredient in concrete. Even though it is important, by volume, it is actually very small. Most of the volume of concrete consists of aggregates—mainly rock, sand, and grit. Cement and water combine to make the paste that holds it all together and creates the strong material that we know.

But when we look at the carbon footprint of concrete, it’s important to note that materials like rock and water have very little impact. It’s the cement that has a massive carbon footprint. Cement is the most prominent material used in construction that emits approximately 6–8% of the total carbon dioxide in the world during its production, making it a major contributor to global warming.

Understanding the Carbon Footprint of Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC)

Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) is associated with significant carbon emissions, with approximately 0.66 to 0.82 kilograms of CO₂ released for every kilogram of OPC produced. The high carbon footprint of OPC is primarily due to two major factors.

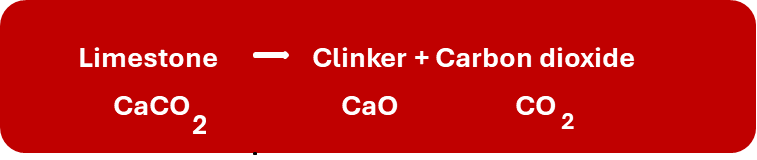

First, the process of calcination, which involves heating limestone (a key raw material), releases a large amount of CO₂. During this chemical reaction, calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) breaks down into calcium oxide (CaO) and carbon dioxide (CO₂). These so-called process emissions account for roughly 55% of the total CO₂ emissions from cement production.

Second, the manufacturing of OPC requires intensive energy use. Raw materials must be heated in a rotating kiln at temperatures reaching approximately 1400°C, contributing to around 38% of the emissions. Additionally, emissions associated with the transport of cement and concrete from production sites to end users are estimated to contribute another 7%.

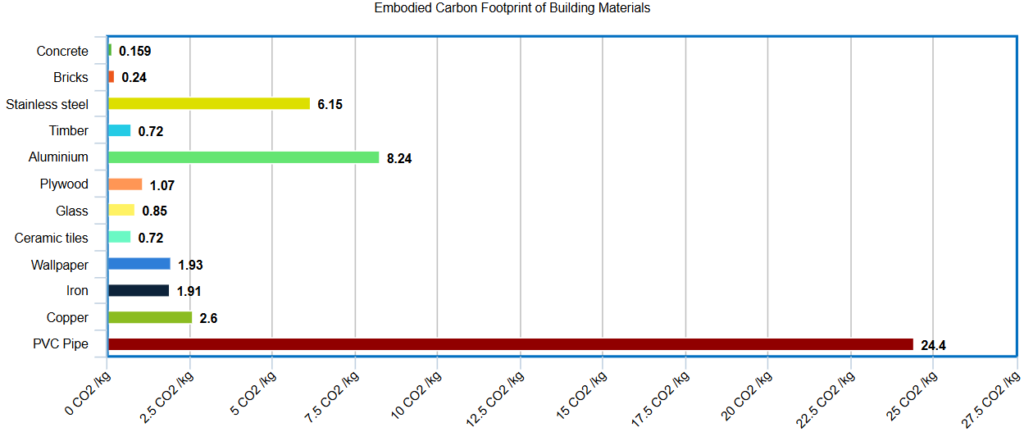

It’s easy to think that concrete is inherently evil and that we should abandon it altogether. However, not actually the case. In fact, when we compare concrete to other construction materials, we can see that concrete is actually a relatively low-carbon material. It has a significantly lower carbon intensity than materials like steel, aluminum, and many others commonly used in construction.

The key issue with concrete isn’t necessarily that it’s a high-impact material—it’s that we use so much of it. Its versatility and strength make it indispensable in modern construction, leading to its widespread use across the globe. The sheer volume of concrete used each year means that, despite its lower carbon intensity compared to other materials, it ends up contributing more to global carbon emissions simply due to the scale at which it’s produced and consumed.

How do we decarbonize concrete?

In an effort to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, the partial replacement of traditional cement has emerged as a key strategy. This approach has led to significant innovations, including the introduction of supplementary cementitious materials such as fly ash, ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS), rice husk ash, and silica fume.

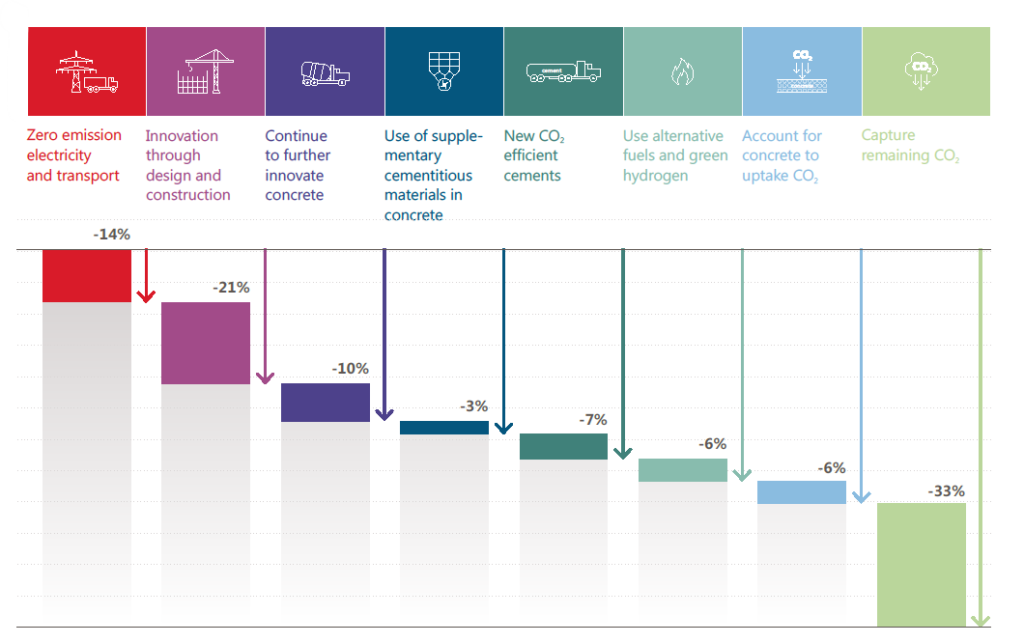

In Australia, the concrete industry has created a decarbonization roadmap that shows how it plans to move from current emission levels to net-zero in the future. This plan includes improving the efficiency of electricity use, transport, and the fuels used in cement production—key areas for cutting emissions.

One part of the roadmap focuses on improving design and construction methods to make buildings and infrastructure more efficient. Another key point is that even after making all these improvements, about one-third of emissions are expected to remain. To deal with this, the industry plans to use carbon capture technologies at the final stage.

The middle section of the roadmap looks at changes to cement and concrete mixes. By adjusting how concrete is made, it’s possible to reduce emissions while still meeting performance and safety standards.

GL Cement

GL cement represents an emerging alternative in the effort to reduce the carbon footprint of cement production. Unlike General Purpose (GP) cement, which consists entirely of traditional Portland cement, GL cement is a blended formulation in which a portion of the Portland cement is replaced with finely crushed, unprocessed limestone. This substitution reduces the energy and emissions associated with cement manufacturing, as the limestone does not undergo calcination or other energy-intensive processing steps.

Although GL cement currently accounts for a relatively small share of the global market, its use is expanding. Notably, countries such as the United States have adopted it more widely as a strategy to reduce the carbon intensity of cementitious materials.

It is important to note that several commonly used Portland cements already permit small additions of limestone. For example:

- In the United States, Type I cement (ASTM C150) may contain up to 5% limestone.

- In Europe, CEM I 32.5 N and CEM I 42.5 N may also include up to 5% limestone.

- In Australia, General Purpose (GP) cement as specified in AS 3972-2010 allows up to 7.5% limestone.

However, these products are not classified as composite cements due to the relatively low proportion of limestone used.

Recent research indicates that concrete produced with cement containing up to 12% limestone shows no significant reduction in compressive strength compared to conventional concrete. These findings demonstrate that performance standards can still be met, even with increased limestone content, supporting the viability of limestone-blended cements as a lower-carbon alternative.

Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCMs)

A similar process is being adopted whereby Portland cement is replaced with supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs). Typically, we utilize two primary products: fly ash and blast furnace slag. These materials are widely used—and for good reason. SCMs are either naturally occurring materials or industrial byproducts that exhibit cementitious properties when combined with water, or with water and other compounds. If not repurposed, many of these byproducts would otherwise be disposed of in landfills or similar sites.

From a decarbonization standpoint, substituting cement with SCMs has been identified as one of the few cost-neutral—or potentially cost-negative—approaches available. SCMs contribute to the overall performance of cement and concrete and can be used to produce mixtures tailored for specific applications.

However, supply poses a significant challenge. These materials are not manufactured specifically for concrete production; instead, we rely on the limited supply generated by other industries. For example, fly ash is a byproduct of coal-fired power plants, which are being phased out globally. As a result, the availability of fly ash is expected to decline substantially in the coming decades. Similarly, blast furnace slag—a byproduct of steel production—is also limited, especially as the steel industry moves toward greener, lower-carbon processes.

Additionally, SCMs are often not available locally and must be transported over long distances—sometimes globally—resulting in additional carbon emissions from transportation.

This highlights a key concern: the current SCM supply is not sustainable in the long term. However, various emerging technologies are being explored to address this issue. Some are at the cutting edge, while others remain in early development stages. Over the coming decade, we expect to see more of these solutions entering the market.

One promising avenue involves the use of natural SCMs, which are produced through controlled heating and purification of specific minerals. These include calcined shale, calcined clay, and metakaolin. A notable example is the recent development in Queensland, Australia where a large-scale mine has been established to produce metakaolin specifically as an SCM. This product offers a significantly lower carbon footprint and represents a promising step forward in sustainable cement production.

Geopolymer Concrete

An important innovation in sustainable construction is the development of geopolymer concrete, which offers a promising alternative to traditional Portland cement-based concrete. Instead of using cement, geopolymer concrete is produced by activating industrial by-products such as fly ash and ground granulated blast furnace slag with alkaline binders. These materials perform a similar function to cement, acting as the primary binder in the concrete matrix.

However, the production of geopolymer concrete involves additional chemical processes, including the use of activators that catalyze the necessary reactions to achieve desired strength and durability. While these activators enable the successful formation of geopolymer binders, their environmental impact must be carefully assessed through a full life cycle analysis. This ensures that the sustainability benefits of geopolymer concrete are not offset by emissions or energy consumption associated with the activator materials.

Although geopolymer concrete does not yet fully conform to traditional design codes, a technical specification has been developed to guide its use in compliance with Australian standards. This specification provides the framework for adapting and validating geopolymer concrete for structural applications, ensuring safety and performance.

Several geopolymer concrete products are now emerging in the Australian market, signaling a growing shift towards low-carbon construction materials. While the material exhibits slightly different properties compared to conventional concrete, it is increasingly recognized for its potential and is beginning to gain traction within the industry.

Codes and Standards for reference

SA TS 199:2023 – Design of Geopolymer and Alkali-Activated Binder Concrete Structures

ASTM C618 – Standard Specification for Coal Fly Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use in Concrete

ASTM C989, Specification for Use in Concrete and Mortars.

ASTM C1240, Specification for Silica Fume Used in Cementitious Mixtures.

ASTM C618, Specification for Coal Fly Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use in Concrete.

AS/NZS 3582.1:2016 – Supplementary cementitious materials – Part 1: Fly ash

AS/NZS 3582.2:2016 –Supplementary cementitious materials, Part 2: Slag – Ground granulated blast-furnace

AS/NZS 3582.3:2022 – Supplementary cementitious materials for use with portland and blended cement, Part 3: Amorphous silica

AS 3582.4:2022 – Supplementary cementitious materials Part 4: Pozzolans

IS 3812 : 2013, Part 1&2

Pingback: Getting Low-Carbon Concrete into Projects -