Soil is formed by the process of ‘Weathering’ of rocks, that is, disintegration and decomposition of rocks and minerals at or near the earth’s surface through the actions of natural or mechanical and chemical agents into smaller and smaller grains. The formation of soil is a very long process; it takes several million years to form a thin layer of soil.

Two main pathways of weathering include physical disintegration and chemical decomposition. Both physical disintegration and chemical decomposition act differently on the parent material, creating recognizable features.

Physical weathering and Chemicl wethering

Physical weathering or mechanical weathering is caused by physical agents such as changes in temperature and pressure, the action of flowing water, ice and wind, and living organisms. Physical disintegration breaks down the rock into smaller pieces and eventually into sand, silt, and clay particles. It predominates in dry and cold environments where the heating and cooling of the exposed rocks create physical stress and cracking.

Soils formed by mechanical weathering bear similarities in certain properties to the minerals in the parent rock, since chemical changes that could destroy their identity do not take place. They generally take place on the surface of the earth.

Rocks are altered more by the process of chemical weathering than by mechanical weathering. Chemical weathering may be caused due to

- Oxidation, in which oxygen ions combine with minerals in the rock, causing the decomposition of rocks;

- Hydration, in which water molecules bind to minerals;

- Hydrolysis, in which the water molecule splits and the hydrogen replaces a cation from the mineral structure;

- Carbonation, in which carbon dioxide in the atmosphere combines with water to form carbonic acid. The carbonic acid reacts chemically with rocks and causes their decomposition; and

- Leaching, where water-soluble parts in the soil, such as calcium carbonate, are dissolved and washed out from the soil by rainfall or percolating subsurface water.

In chemical weathering, some minerals disappear partially or fully, and new compounds are formed. The intensity of weathering depends on the presence of water, temperature, and the dissolved materials in water. Carbonic acid and oxygen are the most effective dissolved materials found in water that cause the weathering of rocks. Chemical weathering is more pronounced in hot and wet climatic regions.

Factors affecting the formation and composition of Soil

Soil is formed by a combination of five factors, called the ‘factors of soil formation’. They are parent material, climate, organisms, topography, and time.

Parent material: The composition of the parent material determines the characteristics of the soil. It influences soil texture and thus many physical properties of the soil, such as the downward movement of water, composition, natural vegetation, and the quantity and type of clay minerals present in the soil profile.

Climate: Climate determines the intensity and type of weathering that occurs on the parent material. The main components of climate that influence soil formation are temperature and precipitation. Both of them affect the rates of physical, chemical, and biological processes that define profile development. Precipitation is necessary because water is required for all the major chemical reactions during the weathering process, and temperature is a factor that increases the rate of soil formation.

Living organisms: Plants, animals, and microorganisms act as factors that influence organic matter accumulation, profile mixing, nutrient cycling, and soil structural stability. Carbon captured through photosynthesis is a source of soil organic matter. Organic matter increases aggregation, porosity, and the water- and nutrient-holding capacity of soils. Organic acids from plant roots play an important role in the chemical weathering of many minerals. Animals also impact this process. Large animals create tunnels and facilitate the movement of water and air. Earthworms, termites, and ants mix the soil, which stimulates soil formation. Human activities, such as the destruction of natural vegetation, tillage, mixing, and compaction, also affect soil formation. Though these effects on the soil are negative, humans can also speed up natural soil restoration processes and minimize soil losses.

Topography: Topography influences the formation, loss, and various properties of the soil. The primary influence of topography is through the impact of the movement of material by erosion from zones of high slope to areas lower in the landscape. Where the products of soil formation are removed through erosion, soil profiles will be shallower, and where the products of erosion are deposited, soils will be deeper.

Time: Time is required for the formation of soil, as it interacts with the other soil-forming processes. The length of time that the parent material has been subjected to weathering affects the soil’s development. When the soil-forming processes have had little time to change the parent material, soil properties will be very similar to the parent material and will contain largely the same original minerals. However, where larger amounts of time have passed, and soil formation has progressed further, the soil may bear no physical or chemical resemblance to the parent material.

Residual and Transported soils

The soil formed by weathering that remains at the place of formation is called residual soil. Those that are transported from their place of origin by various agents such as wind, water, ice, or gravity to new locations are called transported soils.

Residual soils differ significantly from transported soils in their characteristics and engineering behavior. The differences in residual soil characteristics vary both laterally and in-depth due to differences in weathering intensity. The sizes of grains in residual soil are not definite; they comprise a wide range of particle sizes, shapes, and compositions.

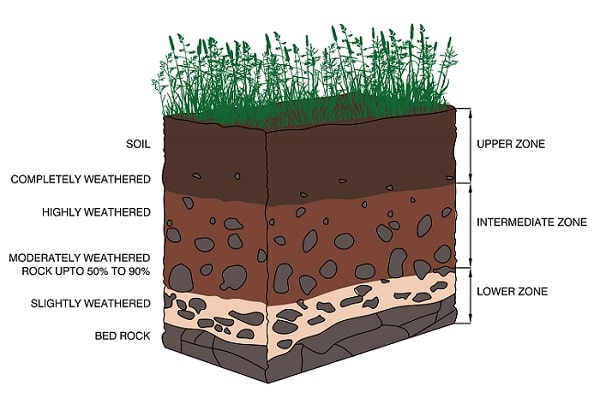

In the weathering process, there is a gradual shift from rock to soil, making it difficult to determine the exact transition from stone to soil. The typical profile of residual soil consists of three zones:

- The upper zone in which the degree of weathering is high. This layer is more likely to be soil.

- The intermediate zone in which the top portion is completely weathered, and the bottom portion is moderately weathered.

- The lower zone, where there is only slight or no weathering. This zone contains fresh rock that has not changed, either in composition or color.

The level of weathering affects the composition of residual soil and is proportional to the depth. The greater the depth of residual soil, the higher the level of weathering and the greater the composition of clay. The sand content decreases as the degree of weathering increases. The main rock contributes to the residual soil composition, while the presence of fine grains is the result of weathering.

The depth of residual soils varies from 5 to 20 meters. They are more abundant in humid and warm zones. These conditions are favorable for the chemical weathering of rocks and there is sufficient vegetation to prevent the products of weathering from being easily transported as sediments. Many regions of the world, such as Africa, South Asia, Australia, Southeastern North America, Central and South America, contain residual soils. Countries like Brazil, Nigeria, South India, Singapore, and the Philippines show the largest areas and thicknesses of these soils.

Transported soils are also referred to as sedimentary soils, as the sediments formed by weathering of rocks are transported by agencies such as wind and water from their original position and deposited when favorable conditions occur. A high degree of alteration to the shape, size, and texture of the grains occurs during transportation and deposition. The typical characteristics of this soil include a large range of grain sizes and a high degree of smoothness and fineness of individual grains.

We can further subdivide transported soils based on the mode of transport and the deposition environment:

- Alluvial soils: Soils transported by rivers and streams (sedimentary clays).

- Aeolian soils: Soils transported by wind (loess).

- Glacial soils: Soils transported by glaciers (glacial till).

- Lacustrine soils: Soils deposited in lake beds (lacustrine silts and lacustrine clays).

- Marine soils: Soils deposited in sea beds (marine silts and marine clays).

Some commonly used soil designations

Some commonly used soil designations, their definitions, and basic properties:

- Bentonite: Decomposed volcanic ash containing a high percentage of the clay mineral montmorillonite. It exhibits a high degree of shrinkage and swelling.

- Black cotton soil: Black soil that contains a high percentage of montmorillonite and colloidal material. These soils are highly compressible and have low bearing capacity. It is named black cotton soil because cotton grows well in it.

- Boulder clay: A glacial deposit that contains boulders of different sizes. It is also known as ‘glacial till.’

- Caliche: A soil conglomerate of gravel, sand, and clay cemented by calcium carbonate.

- Hardpan: A densely cemented soil layer that is largely impervious to water. Boulder clays or glacial tills may also be called hardpan. It is very difficult to penetrate or excavate.

- Laterite: A soil layer that is rich in iron oxide and derived from a variety of rocks weathered under strongly oxidizing and leaching conditions. It is easy to excavate but hardens upon exposure to air due to the formation of hydrated iron oxides.

- Loam: A mixture of sand, silt, and clay-sized particles in roughly equal proportions; sometimes contains organic matter.

- Loess: Uniform wind-blown yellowish-brown silt or silty clay. It exhibits cohesion in the dry condition, which is lost on wetting.

- Marl: A carbonate-rich mud or mudstone containing variable amounts of clays and silt. The clay content is no more than 75%, and lime content is no less than 15%.

- Moorum: Gravel mixed with red clay.

- Varved clay: Clay and silt of glacial origin, essentially a lacustrine deposit. The term ‘varve’ is of Swedish origin and refers to a thin layer.